At the heart of every meal, every farm, and every ecosystem on Earth lies a microscopic engine of civilization: the seed. For over 10,000 years, the relationship between humans and seeds was defined by a sacred, unwritten trust. Farmers were not merely “users” of seeds; they were the stewards of biodiversity, the primary researchers in the world’s longest-running laboratory of genetic adaptation. This “circular economy” of nature created a vast, shimmering tapestry of thousands of varieties of rice, wheat, and vegetables—each uniquely adapted to its local soil, its specific pests, and the erratic rhythms of its climate.

In this ancient paradigm, the seed was a Commons. It was a shared resource that belonged to everyone and no one, a gift from the past intended for the survival of the future. Whether it was the fragrant Basmati of the Himalayan foothills or the drought-hardy maize of the Andean highlands, seeds were saved, selected, and shared with the understanding that life itself cannot be owned.

Table of Contents

The Enclosure of Life

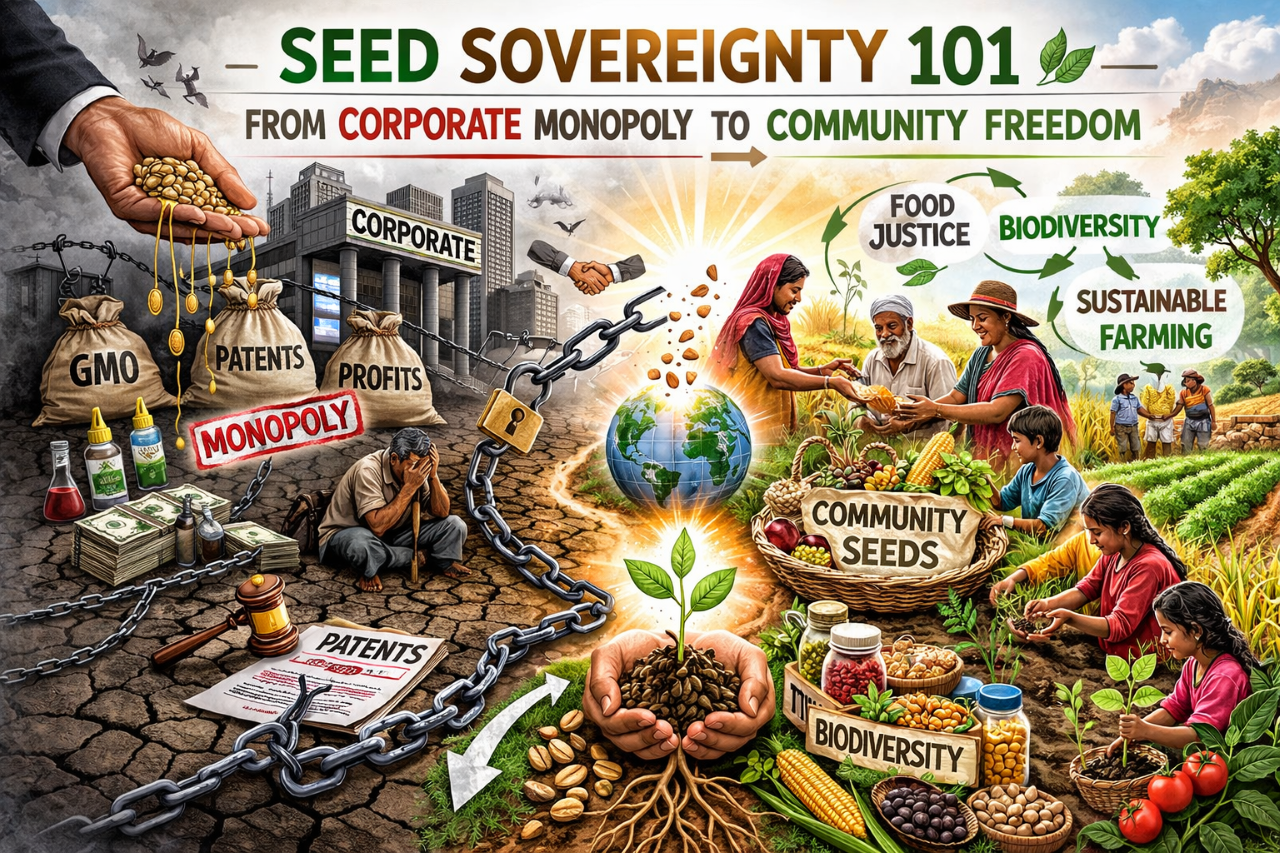

However, the last century has witnessed a radical, aggressive, and historically unprecedented shift. What was once the common heritage of mankind is being rapidly transformed into private intellectual property. We are living through a “legal enclosure” of the biological world, where the foundations of life are being patented, privatized, and genetically modified to serve the profit margins of a handful of multinational corporations.

Today, the global food system stands at a perilous crossroads. On one side is the Industrial Model—a system defined by what Dr. Vandana Shiva calls “monocultures of the mind.” In this paradigm, life is reduced to “software” designed to function only with specific chemical “hardware.” It is a world of standardized, sterile, or chemical-dependent seeds that break the 10,000-year cycle of renewal.

On the other side is the Seed Sovereignty Movement. Led by visionaries like Dr. Shiva and grassroots organizations like Navdanya and La Via Campesina, Seed Sovereignty (or Bija Swaraj) is a global call to reclaim the fundamental right to save, use, and exchange seeds. It is a movement that argues that a seed is not a corporate invention, but a living archive of biological intelligence and a prerequisite for human freedom.

The Primordial Engine—The Biological and Cultural History of the Seed

For eons, the seed has been the quiet architect of our world. To understand the current struggle for Seed Sovereignty, one must first look back at the ten-millennium-long “Golden Age” of agricultural stewardship. This period was characterized by a co-evolutionary dance between human culture and biological intelligence—a partnership that created the very foundation of civilization.

The 10,000-Year Covenant: Co-Evolution as a Sacred Trust

Roughly 12,000 years ago, humanity stood at a crossroads. The transition from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agriculture—the Neolithic Revolution—was not merely a change in food procurement; it was a fundamental shift in the human psyche. We moved from being observers of nature to becoming its primary co-creators.

In the “centers of origin”—the Fertile Crescent (wheat and barley), the Yangtze and Yellow River valleys (rice), the Mesoamerican highlands (maize), and the Andes (potatoes)—our ancestors entered into a silent covenant with the plant world. They realized that by selecting the most vibrant, resilient, and nutritious grains from the wild, they could ensure the survival of their kin.

This was the birth of Seed Stewardship. For 10,000 years, the “technology” of the seed was decentralized and open-source. There were no laboratories or patents. Instead, every farmer was an experimental scientist. By planting seeds in diverse micro-climates—from the rain-shadowed valleys to the sun-scorched plains—farmers engaged in the world’s longest-running experiment in genetic adaptation. This process, known as artificial selection, transformed wild grasses into the staples that feed billions today.

The Seed as a Living Archive: Biological Intelligence

A seed is not an inert commodity; it is a Living Archive. Within its microscopic shell, a seed carries the accumulated memory of thousands of years of human-nature interaction.

Traditional varieties, often called landraces, are unique because they are “population-based.” Unlike industrial seeds, which are bred for identical genetic expression (uniformity), a bag of traditional rice seeds contains high genetic variability.

Adaptability: If a particularly harsh drought hits a field of landraces, some plants will die, but others—carrying specific genetic traits for drought resistance—will thrive. These survivors provide the seeds for the next year, ensuring the crop is always “current” with its environment.

The Memory of Soil: Landraces are “site-specific.” A variety of wheat grown on the slopes of the Himalayas develops different traits than the same variety grown in the delta of the Ganges. This creates a localized biological resilience that no laboratory can replicate.

The Cultural Dimension: Seeds as the Fabric of Society

The history of the seed is also the history of human migration and ritual. In every traditional culture, seeds were treated as “relatives” or “divine gifts.”

India: In the Vedic tradition, the seed is Bija, the source of all potential. It is associated with the goddess Annapurna, the provider of food. Seeds were never just “stuff” to be sold; they were items to be gifted at weddings, shared at festivals, and passed down as heirlooms from mother to daughter.

The Americas: For the Maya and Aztec civilizations, maize was not just a crop; it was the substance of humanity itself. The “Popol Vuh” (Mayan sacred text) claims that humans were literally fashioned out of corn.

The Circular Economy: This cultural reverence led to a Circular Economy of Sharing. Because seeds were viewed as a commons, they moved freely through social networks. This “shuffling of the genetic deck” ensured that biodiversity didn’t just survive—it exploded. At the start of the 20th century, it is estimated that Indian farmers were growing over 200,000 varieties of rice.

The Erosion of the Common Heritage

The 20th century introduced a “linear” logic that sought to break this 10,000-year covenant. The industrial mindset viewed the seed’s ability to reproduce itself as a “market failure.” If a farmer could save their own seeds, a corporation could not sell them new ones.

The shift from Stewardship to Ownership began with the commodification of the seed. By stripping the seed of its cultural and biological history, the industrial model prepared the ground for the “monocultures” we see today. The landraces—the diverse, hardy, and free seeds of our ancestors—were replaced by uniform, fragile, and patented varieties.

The Industrial Rupture—Mechanizing the Farm

The 20th century marked a radical departure from the 10,000-year history of agricultural stewardship. This era saw the transformation of the farm from a self-sustaining ecosystem into a “biological factory.” This shift, often termed the Industrial Rupture, was driven by a post-war surplus of chemical infrastructure and a new, reductionist approach to genetics that prioritized profit and uniformity over resilience and sovereignty.

The Post-War Chemical Pivot: Swords into Plowshares?

The roots of industrial agriculture are found in the wreckage of World War II. During the war, massive industrial capacities were built to produce nitrates for explosives and organophosphates for nerve gas. When the war ended, the “War on Nature” began.

The Nitrate Transition: The same factories that produced bombs were repurposed to produce synthetic nitrogen fertilizers.

The Pesticide Boom: Chemicals designed as weapons of war were rebranded as “pesticides” to kill insects and “herbicides” to kill weeds. The industry realized that traditional, hardy seeds did not “need” these chemicals. To create a market for their chemical products, they needed a new kind of seed—one that was “addicted” to external inputs.

The Green Revolution: Yield at the Cost of Life

In the 1960s, the “Green Revolution” was launched under the guise of humanitarianism. Led by figures like Norman Borlaug, the movement introduced High-Yielding Varieties (HYVs) of wheat and rice to the Global South, particularly India and Mexico. However, Dr. Vandana Shiva argues that the term “High-Yielding” is a misnomer. These seeds are actually “High-Response” varieties. They do not produce high yields on their own; they only produce high yields when doused with massive amounts of synthetic fertilizer and water.

The Collapse of Soil Health: Synthetic fertilizers act like a “drug” for the soil. They provide a quick burst of growth but kill the soil’s microbial life, eventually turning fertile earth into a sterile holding medium.

Water Depletion: HYV seeds often require up to ten times more water than traditional varieties. This led to the catastrophic depletion of groundwater in regions like the Punjab, once known as the breadbasket of India.

The Biological Lock: Breaking the Cycle of Reproduction

To ensure that farmers remained consumers rather than producers, the industry had to find a way to stop seeds from reproducing. They achieved this through two primary methods:

Hybridization: By crossing two distinct inbred lines, corporations created “F1 Hybrids.” These seeds provide high yields in the first year, but the seeds saved from that harvest (the F2 generation) are genetically unstable. If a farmer plants them, the crop will be irregular and low-yielding. This effectively outlawed seed-saving through biology, forcing the farmer back to the market every year.

Genetic Use Restriction Technology (GURT): Popularly known as “Terminator Technology,” this involves genetically engineering seeds to become sterile after the first harvest. While global protests have prevented its widespread commercial use, the intent remains clear: to turn a self-renewing resource into a one-time-use commodity.

The Erosion of Diversity: Monocultures of the Field

The industrial model demands uniformity. Machines are calibrated for plants of the same height, and chemicals are designed for plants with the same genetic makeup. This led to the replacement of thousands of local landraces with a handful of “miracle” seeds.

The Fragility of Uniformity: In an industrial monoculture, every plant is a genetic clone of the other. If a single pest or disease evolves to bypass the resistance of one plant, it can wipe out the entire 1,000-acre field in days.

The Irish Potato Famine Warning: This lack of diversity is what led to the Great Famine in Ireland, where the entire nation relied on a single variety of potato (the Lumper). When the potato blight hit, there was no genetic “backup plan.” By forcing global agriculture into a monoculture, we are setting the stage for a global food collapse.

The Debt Trap: The Social Cost of Rupture

The shift to industrial seeds changed the economics of the farm. In the traditional system, the farmer’s primary inputs—sun, rain, soil, and saved seeds—were free. In the industrial system, the farmer must buy seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides on credit. When the harvest fails or market prices drop, the farmer is left with a debt that cannot be repaid. This “chemical treadmill” has led to a tragic epidemic of farmer suicides across the globe, most notably in India, where over 300,000 farmers have taken their lives since the late 1990s. Seed Sovereignty, therefore, is not just a biological issue; it is a life-and-death struggle for economic justice.

The Legal Enclosure—Patenting the Foundation of Life

The biological “locks” of hybridization and chemicals were only half the battle for corporate control. To fully transform the seed from a common heritage into a private commodity, the global legal system had to be rewritten. This module examines the “Legal Enclosure”—a process where life itself was redefined as “Intellectual Property,” moving the power of creation from the hands of nature and farmers to the boardrooms of multinational corporations.

The Redefinition of Life: From “Product of Nature” to “Invention”

Historically, patent law was designed for mechanical and chemical inventions—steam engines, lightbulbs, or synthetic dyes. Living organisms were explicitly excluded from patentability under the “Product of Nature” doctrine. The logic was simple: no human invented a seed, a cow, or a bacterium; therefore, no human could own the patent to it.

Everything changed in 1980 with the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Diamond v. Chakrabarty.

The Case: Ananda Chakrabarty, a scientist at General Electric, genetically engineered a bacterium capable of breaking down crude oil. The Patent Office initially rejected his application, arguing that micro-organisms are living things and thus not patentable.

The Ruling: In a narrow 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that “the fact that micro-organisms are alive is without legal significance.” They declared that “anything under the sun that is made by man” is patentable. This ruling cracked the legal dam. It redefined the seed not as a living being, but as a “delivery mechanism” for a patented genetic sequence.

The TRIPS Agreement: Globalizing the Monopoly

While Chakrabarty changed U.S. law, the 1994 establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) forced this logic onto every nation on Earth through the TRIPS (Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights) Agreement.

Article 27.3(b): This specific clause of TRIPS requires all member nations to provide intellectual property protection for plant varieties, either through patents or a “sui generis” (of its own kind) system.

The Corporate Architects: Dr. Vandana Shiva often points out that TRIPS was not written by governments, but by a coalition of twelve corporations (including Monsanto, DuPont, and Syngenta). They acted as “the patient, the diagnostician, and the physician all in one,” crafting a treaty that criminalized the ancient practice of seed-saving to create a global market for their products.

Biopiracy: The Theft of Indigenous Knowledge

“Biopiracy” is the practice of corporations using intellectual property laws to claim ownership over resources and knowledge that have belonged to indigenous communities for centuries. Dr. Shiva’s legal team has led the global fight against several high-profile cases of biopiracy:

The Neem Case: For 2,000 years, Indians used the Neem tree as a pesticide and medicine. In 1994, the U.S. company W.R. Grace received a European patent on a fungicidal extract of Neem. Dr. Shiva and a coalition of NGOs fought this for ten years, arguing that there was no “novelty”—it was ancient knowledge. They won, and the patent was revoked in 2005.

The Basmati Case: In 1997, a Texas-based company called RiceTec was granted a patent on “Basmati rice lines and grains.” Basmati has been grown in the Himalayan foothills for millennia. By claiming they had “invented” it, RiceTec could have prevented Indian and Pakistani farmers from exporting their own rice. After a massive global outcry and legal challenge, most of the claims were struck down.

The Schmeiser Case: Property Rights vs. Biological Reality

The most chilling example of the legal enclosure is the case of Monsanto v. Schmeiser (2004). Percy Schmeiser, a Canadian canola farmer who had never bought Monsanto seeds, found that his fields were contaminated with “Roundup Ready” canola. The seeds had blown onto his land from a neighbor’s truck or been carried by the wind. Instead of apologizing for contaminating his organic crop, Monsanto sued him for “patent infringement.”

The Canadian Supreme Court ruled in favor of Monsanto. Their logic was devastating: It did not matter how the seeds got there. Because Schmeiser’s crop contained Monsanto’s patented gene, he was technically in “possession” of their property. This ruling established that corporate property rights override the biological reality of cross-pollination and the rights of the farmer.

The Enclosure of the Future

By turning seeds into “Intellectual Property,” corporations have achieved what feudal lords could only dream of: they have enclosed the very source of life.

Criminalization: In many countries, the exchange of non-patented, traditional seeds is now being “regulated” out of existence.

Data-Mining Life: Today, the enclosure is moving into “Digital Sequence Information” (DSI), where corporations sequence the DNA of seeds and patent the digital code, ensuring that even without the physical seed, they own the biological blueprints of our planet.

“Monocultures of the Mind”—The Philosophical Struggle

The transition from a world of shared seeds to one of corporate patents did not happen in a vacuum. It was preceded and accompanied by a profound shift in how humanity perceives nature, knowledge, and intelligence. Dr. Vandana Shiva identifies this as the rise of “Monocultures of the Mind.” This module explores the philosophical warfare between the mechanistic worldview of industrialism and the organic, holistic paradigm of Seed Sovereignty.

The Mechanistic Paradigm: Nature as a Machine

Since the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, Western science has increasingly viewed the world through a “mechanistic” lens. In this paradigm, nature is not a living, self-organizing system; it is a machine composed of inert parts that can be manipulated for human ends.

- The Reductionist Fallacy: Reductionism argues that to understand a system, you must break it down into its smallest parts. When applied to agriculture, a forest is reduced to “timber,” a farm is reduced to a “food factory,” and a seed is reduced to a “delivery mechanism” for genetic code.

- The Erasure of Life: By treating the seed as a machine, we ignore its inherent “subjectivity”—its ability to evolve, adapt, and reproduce. In the mechanistic view, the seed is “passive” until acted upon by the “active” scientist in a lab.

Defining “Monocultures of the Mind”

Dr. Shiva’s concept of “Monocultures of the Mind” describes a state where the diversity of human knowledge is destroyed to make way for a single, dominant way of thinking.

- The Destruction of Local Knowledge: Indigenous and traditional farming knowledge—often held by women—is dismissed as “primitive” or “unscientific” because it cannot be quantified by industrial metrics.

- The Illusion of Universal Truth: Industrial science claims its methods are “universal,” but they are often only “local” to a laboratory setting. A seed that performs well in a controlled, chemical-rich environment often fails in the complex, erratic conditions of a real-world field.

- The Blindness to Consequences: When we focus only on a single variable (like “yield”), we become blind to the “externalities”—the destruction of soil health, the poisoning of water, and the collapse of rural communities.

The Patriarchy of the Seed

Seed Sovereignty is also a feminist struggle. In most traditional cultures, women have been the primary seed-keepers. They managed the biodiversity of the kitchen garden and the long-term storage of grains.

- The Shift in Power: The industrialization of seeds moved the seat of knowledge from the home and the field (the domain of women) to the laboratory and the boardroom (historically the domain of men).

- The Devaluation of Care: The organic paradigm is based on “care” and “nurturing” the soil. The industrial paradigm is based on “control” and “domination” over nature. To reclaim the seed is to reclaim the “feminine” principle of sustaining life.

Knowledge Sovereignty: Reclaiming “Indigenous Science”

The movement for Seed Sovereignty argues that there is no single “science.” Instead, there is a “Biodiversity of Knowledge.”

- The Scientist-Farmer: A farmer who knows which variety of rice can survive a salt-water surge or which bean repels a specific beetle is a scientist. Their laboratory is the field, and their peer-review process is the survival of their community over generations.

- Cognitive Justice: Seed Sovereignty demands “cognitive justice”—the recognition that traditional knowledge systems are just as valid and “scientific” as Western laboratory science, often proving more resilient in the face of climate instability.

The Path to Intellectual Liberation

The “Enclosure of the Mind” is the first step toward the “Enclosure of the Seed.” To fight for Seed Freedom, we must first liberate our minds from the belief that:

- Diversity is “inefficient.”

- Uniformity is “progress.”

- Life can be “invented” and “owned” by a corporation.

By reclaiming the “Organic Paradigm,” we begin to see the seed not as a commodity to be exploited, but as a teacher and a bridge to a sustainable future. As we move to Module 5, we will see how this philosophy is put into practice through the creation of Community Seed Banks.

The Navdanya Model and Community Seed Banks

While the legal battles described in earlier modules take place in the sterile environment of courtrooms and international trade summits, the true heart of the Seed Sovereignty movement beats in the soil. Dr. Vandana Shiva founded Navdanya (meaning “Nine Seeds” or “New Gift”) in 1987 as a direct response to the encroaching threat of industrial seed monopolies. The core of this practical resistance is the Community Seed Bank.

This module explores the mechanics, science, and social brilliance of the seed bank model, which serves as a living library of biological intelligence and a frontline defense against climate change.

In-Situ vs. Ex-Situ: Why Living Seeds Matter

To understand the Navdanya model, one must distinguish it from the “Doomsday Vault” model, such as the famous Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway.

- Ex-Situ Conservation (The Vault): Svalbard freezes seeds in a mountain to preserve them for a catastrophic future. While valuable as a backup, these seeds are “frozen in time.” They do not grow, they do not interact with the soil, and they do not adapt.

- In-Situ Conservation (The Living Bank): Community seed banks keep seeds in the hands of farmers. Because seeds are living organisms, they must be planted, grown, and harvested regularly. This allows them to co-evolve with changing rainfall patterns, new pests, and rising temperatures. In a warming world, a seed that was frozen 40 years ago may be “genetically obsolete” upon thawing. A seed that has been grown every year for 40 years has learned how to survive.

The Mechanics of a Community Seed Bank

A community seed bank is far more than a storage shed; it is a social and biological institution. Navdanya has established over 150 of these banks across India, and the model has been replicated worldwide.

- The Collection Phase: Farmers and researchers travel to remote villages to find “landraces”—traditional varieties that have been nurtured for generations. They look for seeds with specific “virtues,” such as deep roots, medicinal properties, or fragrance.

- The Multiplication Phase: These seeds are planted in “conservation plots.” These plots are strictly organic, ensuring the seeds are not “coddled” by chemicals. This tests the seed’s inherent strength and resilience.

- The Exchange Phase: This is the “Bija Swaraj” in action. The bank does not sell seeds. Instead, it operates on a Non-Monetary Exchange. A farmer “borrows” a certain amount of native rice seeds and, after the harvest, returns double that amount to the bank. This ensures the “biological capital” of the community grows every year without the need for cash or debt.

Breeding for Resilience: The Science of Survival

Industrial seeds are bred for a “protected” environment—one where humans provide the water and chemicals. Navdanya’s seeds are bred for the unprotected reality of a changing planet.

- Flood-Tolerant Varieties: In the wake of increasing cyclones in Orissa and West Bengal, Navdanya has conserved “Balu” and “Bhundi” rice, which can remain submerged under floodwaters for weeks and still produce a harvest.

- Salt-Tolerant Varieties: As sea levels rise, salt-water intrusion is destroying coastal farms. Traditional “Kala” rice varieties thrive in saline soils, providing a lifeline for coastal communities where industrial “miracle” seeds simply wither and die.

- Drought-Resistant Grains: Millets and ancient wheats are being revived because their deep root systems allow them to find water in parched earth, making them the “climate heroes” of the 21st century.

The Role of Women: The Grandmothers’ Science

In the Navdanya model, women are the primary decision-makers. Historically, women have been the guardians of the kitchen and the field. They know which seed variety is easy to grind, which one keeps the family full longer, and which one resists mold in the granary. By putting the seed bank in the hands of women, the movement ensures that Nutritional Sovereignty is prioritized over “Yield per Acre.” It also restores the social status of women as the primary “scientists” of the community.

From Seed Banks to Seed Freedom Zones

The ultimate goal of the Navdanya model is to create Seed Freedom Zones. These are entire villages or regions that declare themselves free from patented seeds and chemical fertilizers.

- Ecological Security: These zones become “bio-hotspots” where birds, bees, and beneficial insects return, restoring the natural balance that was destroyed by pesticides.

- Economic Independence: By producing their own seeds and fertilizers (compost, vermiculture), farmers in these zones are debt-free. Their “profit” may be lower on paper than a high-input industrial farm, but their net income is higher because their costs are zero.

The Economics of Debt & The Satyagraha of Hope

The struggle for Seed Sovereignty is often framed as a biological or environmental issue, but at its core, it is a struggle against a predatory economic system. To control the seed is to control the “debt-gate” of the global food system. This module examines the mathematical reality of industrial farming, the tragic consequences of the “credit-seed-chemical” treadmill, and the revolutionary non-violence of the Seed Satyagraha.

The Anatomy of the Debt Trap

In the traditional farming model, a farmer’s primary inputs were what Dr. Shiva calls “Gifts of Nature”: sun, rain, soil fertility from compost, and the seeds saved from the previous harvest. In this “Circular Economy,” the cost of production was nearly zero.

The industrial model transformed the farmer into a consumer. To participate in the modern market, a farmer is forced to buy:

- Patented Seeds: Which are expensive and cannot be legally or biologically saved.

- Synthetic Fertilizers: Required because industrial seeds are “addicted” to high nitrogen levels.

- Pesticides & Herbicides: Required because monocultures lack the natural checks and balances of a diverse ecosystem.

Because these inputs require significant capital, the farmer must take out loans—often from private moneylenders or corporate-linked banks at high interest rates. When a harvest fails due to a changing climate, or when global commodity prices drop, the farmer is left with a debt that is mathematically impossible to repay.

The Epidemic of Farmer Suicides

This economic structure has led to one of the greatest humanitarian tragedies of the 21st century. In India alone, more than 300,000 farmers have committed suicide since 1995. This epidemic is concentrated in the “cotton belt,” where the transition to Bt Cotton (Monsanto’s genetically modified variety) was most aggressive.

The tragedy of the “suicide seed” lies in the loss of agency. When a farmer loses the right to save seeds, they lose their autonomy. Dr. Shiva points out that these are not just “suicides”—they are “corporate homicides” caused by an economic system that prioritizes patent enforcement over human life.

True Cost Accounting: Exposing the “Cheap Food” Myth

Industrial agriculture claims to be “efficient” because it produces large volumes of a single commodity at a low market price. However, Seed Sovereignty advocates use True Cost Accounting to show that industrial food is actually the most expensive food in history.

- Externalities: The “low price” of industrial grain does not include the cost of cleaning pesticide-polluted groundwater, treating cancer in farming communities, or the trillions of dollars lost in “ecosystem services” as pollinators die off.

- The Productivity of Diversity: Navdanya’s research shows that organic, biodiverse farms produce more nutrition per acre than industrial monocultures. While an industrial farm may produce more “tons of starch,” a sovereign farm produces a balanced diet of proteins, minerals, and vitamins, making it more economically viable for the health of the nation.

Seed Satyagraha: Civil Disobedience for Life

In the face of this economic violence, Dr. Shiva launched the Seed Satyagraha. The term comes from Mahatma Gandhi’s Satyagraha (Truth-Force). Just as Gandhi marched to the sea to protest the British salt tax—arguing that salt is a gift of nature and cannot be taxed—the Seed Satyagraha declares that seeds are a gift of nature and cannot be patented.

The Principles of Seed Satyagraha:

- Non-Cooperation: Farmers openly declare that they will not obey laws that criminalize seed-saving. When the law is “inherently violent” to the Earth and the poor, it is a moral duty to break it.

- Seed-Sharing as Resistance: The act of exchanging seeds with a neighbor becomes a political act. It is a refusal to let the market define the value of life.

- GMO-Free Zones: Entire communities declare their land a “Sovereign Territory,” where corporate patents and genetically modified organisms are prohibited.

From Scarcity to Abundance

The industrial model is built on the manufactured scarcity of patented life. Seed Sovereignty is built on the natural abundance of the living seed. By breaking the cycle of debt, the Seed Satyagraha restores the farmer’s dignity. It moves the goal of farming from “servicing a loan” to “nourishing a community.”

The Global Battlefield—International Treaties & Rights

While farmers practice resistance in the soil, a parallel and equally fierce struggle occurs within the glass-walled headquarters of international organizations. This is the “Global Battlefield,” where legal frameworks are debated that can either legitimize the corporate enclosure of life or protect the ancient rights of the peasantry. This module analyzes the clash between “Breeder’s Rights” (corporate interests) and “Farmers’ Rights” (sovereignty), and the international treaties that govern the global genetic commons.

The Conflict of Two Worlds: UPOV vs. The Seed Treaty

In the international legal arena, two primary frameworks compete for dominance. They represent fundamentally different visions of what a seed is and who it belongs to.

UPOV 91 (The Corporate Gold Standard): The International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), specifically the 1991 Act, is designed to protect “Plant Breeders.” To be eligible for protection under UPOV, a seed must meet the DUS Criteria: it must be Distinct, Uniform, and Stable.

The Trap of Uniformity: Traditional landraces are excluded from UPOV because they are diverse and evolving—they are not uniform. By making “Uniformity” a legal requirement for protection, UPOV effectively mandates the destruction of biodiversity.

Criminalizing Exchange: UPOV 91 severely restricts the “farmer’s privilege.” In many countries that have signed this treaty, it is illegal for a farmer to sell or even exchange seeds of a protected variety with their neighbor.

The Seed Treaty (ITPGRFA – The People’s Shield): Formally known as the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, this 2004 treaty was a hard-won victory for the Seed Sovereignty movement. It is the first international legally binding instrument to recognize Farmers’ Rights (Article 9).

The Global Commons: The treaty established a multilateral system for 64 of the world’s most important food crops, ensuring they remain in the public domain for research and breeding.

Defining Farmers’ Rights: The Four Pillars

The Seed Treaty outlines four critical rights that are essential for Seed Sovereignty. However, these rights are often undermined by trade agreements like TRIPS.

- Protection of Traditional Knowledge: Recognizing that the “science” of the indigenous farmer is as valuable as the laboratory scientist.

- Equitable Benefit Sharing: If a corporation uses a traditional seed to create a new commercial variety, the community that originally nurtured that seed must receive a share of the profits.

- Participation in Decision-Making: Farmers must be at the table when national and international seed laws are drafted.

- The Right to Save, Use, Exchange, and Sell: This is the core of Bija Swaraj. However, the treaty contains a loophole that makes this right “subject to national law,” which often leads back to corporate-dominated UPOV rules.

The WIPO Battle: Digital Biopiracy (DSI)

The newest frontier in the global battlefield is Digital Sequence Information (DSI). Corporations are now sequencing the DNA of traditional seeds and uploading them to digital databases.

- Synthetic Biopiracy: By patenting the “digital code” of a seed, a company can use synthetic biology to recreate the plant’s traits in a lab without ever touching the physical seed.

- The Legal Loophole: Because current treaties (like the Nagoya Protocol) focus on physical access to biological material, digital sequences exist in a “legal gray area,” allowing corporations to bypass benefit-sharing requirements.

The UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants (UNDROP)

In 2018, the United Nations adopted UNDROP, a landmark declaration that solidifies seed sovereignty as a human right.

- Article 19: Explicitly states that “Peasants and other people working in rural areas have the right to seeds,” including the right to protect traditional knowledge and the right to maintain their own seed systems.

- The Shift in Logic: This moves the debate from “Property Law” to “Human Rights Law.” It argues that access to seeds is a prerequisite for the Right to Food, and therefore cannot be overridden by corporate patents.

Reclaiming the Global Commons

The global battlefield is currently a stalemate. Corporations use trade sanctions and bilateral agreements (FTAs) to force UPOV 91 on developing nations. Meanwhile, the Seed Sovereignty movement uses the UN and the Seed Treaty to build a “Global Commons.” The future of food depends on which legal logic prevails: the logic of the market or the logic of life.

Reclaiming the Future—Earth Citizenship

The struggle for Seed Sovereignty is far more than a technical debate over agricultural inputs or patent law; it is the frontline of a global movement to define what it means to be a “living” society. This final module explores the transition from being a consumer in a corporate food chain to becoming an Earth Citizen, and offers a vision for a future where life is once again free to renew itself.

From Food Consumer to Earth Citizen

The industrial model has spent decades training us to be “consumers”—passive endpoints in a global supply chain who prioritize low prices and year-round availability over health, ecology, and justice. Seed Sovereignty asks us to shed this identity and embrace Earth Citizenship.

- Interconnectedness: An Earth Citizen recognizes that every bite of food is a political and ecological act. If a seed is patented and the soil is poisoned, the food cannot be truly nourishing.

- Responsibility: Sovereignty is not just a right; it is a responsibility to protect the biodiversity that sustains us. This means supporting local seed banks, demanding GMO labeling, and resisting the “Monocultures of the Mind.”

The GMO-Free Zones: Living Landscapes of Peace

Across the world, communities are declaring their territories “GMO-Free Zones” and “Seed Freedom Zones.” These are not just symbolic declarations; they are practical “Zones of Peace” where the war on nature has been called to a halt.

- The Return of Life: In these zones, the removal of synthetic pesticides and patented monocultures leads to an immediate explosion of life. Pollinators return, groundwater stabilizes, and the “biological intelligence” of the landscape begins to repair itself.

- The New Peasantry: A new generation of “young peasants”—urbanites moving back to the land—is using Seed Sovereignty as the foundation for a “New Agrarianism.” They are combining traditional seed-saving with modern ecological science to create hyper-productive, small-scale farms.

The Future is Diverse, Local, and Adapted

As the world faces the dual crises of climate change and disappearing biodiversity, the “standardized” industrial seed is failing. The future belongs to the diverse and the adapted.

- Climate Resilience: We cannot predict the exact weather patterns of 2050. Therefore, we must save as many varieties as possible. Biodiversity is the “genetic library” that contains the solutions to problems we haven’t even encountered yet.

- Decentralization: By moving the power of the seed from five global corporations to five million local seed banks, we create a food system that is “anti-fragile”—one that can withstand global shocks because it is rooted in local sovereignty.

The Radical Act of Hope

The act of saving a single heirloom seed may seem small in the face of billion-dollar corporations and international trade treaties. However, in an era of corporate enclosure, it is one of the most radical acts of resistance available to us.

When we protect the freedom of the seed, we protect the freedom of all life to evolve, to renew, and to thrive. The seed is a bridge between the wisdom of our ancestors and the survival of our descendants. It reminds us that:

- Life is not an invention: Nature’s intelligence cannot be “owned” by a boardroom.

- Diversity is Strength: The more varieties we save, the more tools we have to survive.

- Food is a Right, Not a Commodity: The foundation of our nourishment must remain in the hands of those who tend the soil.

The “Seed Satyagraha” is not just a protest against the past; it is a celebration of the future. By reclaiming the seed, we reclaim our story, our health, and our freedom. As Dr. Vandana Shiva often says, “The seed is the site of our liberation.” It is time to plant the seeds of a new world, one grain at a time.